In Books: Jewish Exodus from Iraq Revisited

A number of recent novels have addressed the relationship between Muslim, Christian, and Jewish populations of Baghdad. Iraqi writer Ali Shakir tells his story:

By Ali Shakir

Who would have thought?

At the age of ten, I took to the stage in my primary school in Baghdad to recite verses that called for an immediate liberation of Palestine’s land from the vicious Jewish occupation. My short poem was met with a roar of applause, I felt ecstatic. … Thirty-six years after what I’ve considered a glorious moment in my life; my comprehension of the notion of animosity has noticeably changed, and here I am, writing about Jewish writers and the injustice done to their people. But wait! Passports aside; the Jews I’m talking about are no less Iraqi than I am. They were born, grew up and studied in Baghdad just as I did, and we both migrated from Iraq—albeit in different times—when life there became unbearable for us and our families.

At the age of ten, I took to the stage in my primary school in Baghdad to recite verses that called for an immediate liberation of Palestine’s land from the vicious Jewish occupation. My short poem was met with a roar of applause, I felt ecstatic. … Thirty-six years after what I’ve considered a glorious moment in my life; my comprehension of the notion of animosity has noticeably changed, and here I am, writing about Jewish writers and the injustice done to their people. But wait! Passports aside; the Jews I’m talking about are no less Iraqi than I am. They were born, grew up and studied in Baghdad just as I did, and we both migrated from Iraq—albeit in different times—when life there became unbearable for us and our families.

My first encounter with the plight of the Iraqi Jews was in 2007 when Saudi-owned, London-based news website Elaph ran a series of essays by Shmuel Moreh—professor emeritus in the Department for Arabic Language and Literature at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Reading the intimate recollection of stories on my laptop screen triggered memories of the beautiful villas I’d driven by on my way to the university. The British-colonial-style buildings, I was told, belonged to wealthy Jewish families, but were confiscated by the government after their owners had fled the country to Israel in the early 1950s.

Tormented by the past, struggling to adjust to an ever-changing, ever-challenging present; the fresh immigrant that I was at the time could relate to the nostalgia in professor Moreh’s pieces, but found them unrealistically sterile for a man who’d been wronged and forced off the land of his ancestors. How could there not be even a hint of anger or blame? I couldn’t understand. The stories, nonetheless, managed to pique my interest. I started looking for more information about what might have caused the mass migration of Jews from Mesopotamia; the land where they’d established their first diaspora community, following the Babylonian captivity.

A guiding thread came unexpectedly from my mother, who turned out to have had a Jewish childhood friend named Evelyn. The two little girls bid tearful farewell at my grandmother’s while an angry mob screamed obscenities against “the filthy Jews” aloud in the street, my mother told me. I decided to include Evelyn’s story in my then unfinished book A Muslim on the Bridge and went on searching for other firsthand testimonials.

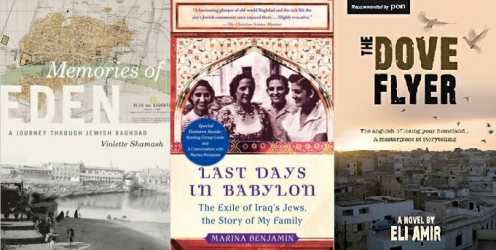

I was visiting the Middle East in 2011, when—unexpectedly, again—Ghada, my Jordanian friend of Palestinian descent recommended Memories of Eden: A Journey Through Jewish Baghdad (Northwestern University Press, 2010) a collection of letters, sent by Violette Shamash to her daughter, Mira, and journalist son-in-law Tony Rocca, who together edited the stories into an impressive memoir. I remember going through the pages and photographs as if I were watching a fascinating documentary. Shamash’s letters gave me an insight into what happened during the infamous Farhud—an unprecedented series of attacks against Baghdad’s Jewry, following a failed pro-Nazi coup in 1941.

The indiscriminate rape, killing and pillage that went on for two consecutive days not only marked the end of a centuries-long honeymoon between the Muslims and Jews in Iraq, they are also thought to have resulted in the spread of Zionism amongst the young members of the community, the majority of which had so far opposed Jewish immigration to Palestine and refused to consider any country other than Iraq to be their eternal homeland. … I needed to learn more about the sudden shift in loyalties, how it started and evolved.

Upon browsing the library shelves in Auckland a few years ago; I found Last Days in Babylon: The History of a Family, the Story of a Nation (Free Press, 2006) by journalist Marina Benjamin who admits that she only became interested in the legacy of her forebears after giving birth to her first child. The riveting moment made her aware of the widening gap between her past and present, and set out on an ambitious mission to bridge it. With a British passport in hand, Marina arrived in Baghdad decades after the bitter departure of her mother and grandmother to trace whatever might have remained there of their history. Sadly, there wasn’t much, not even a marker to identify her grandfather’s grave.

Benjamin didn’t return empty-handed from Baghdad, though. She visited the last standing synagogue, and—with understandable difficulty—managed to convince the few remaining Jews in the city to speak to her. Their accounts of the hardships that had befallen them and their families over the past decades and the miserable lives they were leading shed light on several corners of their people’s history and haunted me long after finishing the book.

Up until that point, I’d deliberately steered clear of novels. Facts were my main focus, and I was keen not to allow the allure of fictitious affairs to distract me from them. My inquisitive approach to the truth provided me with a considerable amount of information, but it also left me confused, feeling like a child surrounded by scattered jigsaw puzzle’s pieces, clueless as to how to assemble them into a complete picture. I thought it was probably time to turn to fiction for help. … Having familiarized myself with events, places and key political players and atmosphere; I glided to a smooth landing on the epoch of The Dove Flyer by Eli Amir, translated from Hebrew by Hillel Halkin (Halban Publishers, 2010).

The novel is set in 1950 Baghdad. Two years have passed since the declaration of the establishment of Israel in Palestine. An anti-Jewish sentiment is sweeping the city streets, and the consequences of the Farhud continue to snowball, causing a serious rift in the community. To his credit, Eli Amir casts no halo about any faction. Rather, he gives us a stark portrayal of the blustery political and social scene in an eloquent, epic-like monologue which extends across several pages: After surviving an attack by a furious crowd of fellow-Jews, Rabbi Bashi vents frustration over his ungrateful and impossible to please community, the Zionists, the Communists, the Muslims, Iraqi royals and politicians, even The Master of the Universe.

The Dove Flyer not only stands out as a decent work of literature, but also and most importantly as a vivid historical document. It made me relive the intensity of the pressures and threats imposed on its characters, and realize that their exodus from Iraq was a desperate act of survival rather than a lack of patriotism, even treason—as described in our school history books. … “We’ve lived with the Jews longer than anyone can remember. Let no one touch them!” I quote Khayriiya from the novel—a simple Muslim woman, who comes to her longstanding neighbors’ rescue, positioning herself at their gate and yelling at the rioters—and wonder.

Iraqi-born, New Zealander architect and author of A Muslim on the Bridge (Signal 8 Press, 2013) and Café Fayrouz (ASP Inc. 2015).

Jewish Exodus from Iraq Revisited | band annie's Weblog

September 21, 2016 @ 6:32 am

[…] mlynxqualey Arabic Literature (in English) | September 21, […]

September 21, 2016 @ 7:08 am

Thank you for this insightful article. I was fortunate to be contracted with the translation into French of Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi, released in libraries on 1 September. (see here: http://www.piranha.fr/livre/frankenstein_a_bagdad) . It touches on your subject, as Baghdad Jewish quarter serves as a backdrop to the intrigue and the plurality of cultures and religions intertwines tightly with the plot of the novel. I strongly recommend this novel to anyone interested in life in Baghdad, past or present. For non-Arab speakers, the English translation should come out soon. For an English review of the novel, see here: http://cais.anu.edu.au/story/frankenstein-baghdad-ahmad-saadawi.

Kind regards,

France

September 21, 2016 @ 2:54 pm

Thank you! Of course readers can also enjoy the review from ArabLit. 🙂

https://arablit.org/2014/02/06/a-golden-piece-of-shit-on-morality-and-war/

September 21, 2016 @ 1:54 pm

A germinal book on this subject is Naïm Khattan’s Adieu Babylone, written in French, a memoir by an Iraqi Jew born in the early 1930s who describes a society where the young, students, at least, were integrated, and its disintegration. Resistant to Zionism, Khattan went to France to study, and then immigrated to Canada, where he still lives, and I believe served as Minister of Culture.

September 21, 2016 @ 2:58 pm

Thank you, Marilyn.

September 21, 2016 @ 4:19 pm

Reblogged this on kalimat2016 and commented:

I love this!

September 21, 2016 @ 7:19 pm

Thanks for this piece. I grew up in a neighborhood in Karada where we had Jewish and Christian neighbors. These days may come back.The Revisiting also found expressions in books about Jewish cuisine in Iraq.

September 21, 2016 @ 7:34 pm

May those days return.