Michael Mohammed Ahmad’s ‘The Lebs’: Depicting Arab Lives in Australia

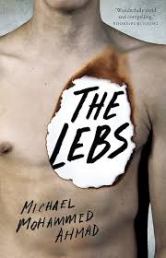

Michael Mohammed Ahmad — author and founder of ‘Sweatshop: Western Sydney Literacy Movement” — is launching a new novel, The Lebs, on February 27:

By Hend Saeed

Ahmad’s essays and short stories have appeared in the Sydney Review of Books, The Guardian, The Australian, Heat Seizure, The Lifted Brow, Meanjin and Best Australian Essays, and his debut novel, The Tribe (Giramondo, 2014), received the 2015 Sydney Morning Herald Best Young Australian Novelist of the Year Award. He also adapted The Tribe for the stage.

Ahmad’s essays and short stories have appeared in the Sydney Review of Books, The Guardian, The Australian, Heat Seizure, The Lifted Brow, Meanjin and Best Australian Essays, and his debut novel, The Tribe (Giramondo, 2014), received the 2015 Sydney Morning Herald Best Young Australian Novelist of the Year Award. He also adapted The Tribe for the stage.

His new novel, The Lebs, is being launched next week.

Michael Mohammed Ahmed: Like many Lebanese families who arrived in the 1970s, my grandparents immigrated to Australia. My grandfather originally was from Syria, but lived in Lebanon.

My parents arrived Australia when they were between seven and nine years old, and they met in Sydney when they were 22.

Life wasn’t easy for my grandparents and my parents, as it wasn’t for many Lebanese families at that time, and they worked hard to give my brothers and I access to higher education.

HS: You are the founder and director of “Sweatshop: Western Sydney Literacy Movement.” What is the aim of Sweatshop? And why it is for western Sydney ?

MMA: The movement started in 2006 when I established Westside. I got a scholarship to prepare my doctorate, and I used some of the money to start Westside. Then, in 2013, I established Sweatshop to continue the work on a larger scale.

The aim of the movement is to teach young people creative writing and cultural representation and to help them to find hope through writing. I chose “Western Sydney” because it has a diverse community. Some even call it “Sydney Others.”

I consider the program a transition period in the lives of these young ethnic writers. Writing helps them to educate themselves and shift their thinking from computer games and their troubled lives to their writing and changing the world around them. By changing the lives of young people, we can change the world’s perceptions of them.

These young people still face a lot of problems from the community and we need to restore the community’s confidence in them.

HS: Your first novel The Tribe won the Sydney Morning Herald Best Young Australian Novelist of the Year award in 2015. Can you tell us something about that novel?

MMA: The Lebanese community in Australia, unfortunately, are featured in the media as a culture of crime, assault, and drugs. This idea came about because many Lebanese families who immigrated to Australia in the 1970s had informal educations and were unemployed, and that created some problems, as it does in any community in the same circumstances. After that came the events of 2000 and the 2005 riot.

Now the third generation of these families are educated, employed, and participating in the community, but the media — and people’s perceptions — haven’t changed. The Lebanese have to work hard to prove themselves.

I wrote The Tribe to show the other side of this community — the day-to-day lives of Lebanese families who are like any other families, have problems and challenges in life. I wanted to normalize the Arab Muslim identity in Australia.

The award is very special to me; first, because it is the recognition of my writing in Australia; and second because, that year, the award was given to myself and others five from minority groups — Asian, Malaysian, African — and that’s what made it special.

These minority groups, including Arabs, are changing the face of Australian literature.

HS: Your new novel The Lebs is about Lebanese as well. Is it a sequel to The Tribe?

MMA: Yes, it is almost a sequel to The Tribe. It is the story of Bani Adam, and, in The Tribe, I talked about his life from the age of 7 to 11. In The Lebs, he’s 14 to 19 years old.

But let me explain something about the term “The Lebs” and how it’s used in Australia. This term was created to depict a group of young people from different ethnic groups who walk, dress, and speak Arabic or English in a particular way. They can be Jordanian, Iraqi, Lebanese, even Malaysian.

They have created a unique new identity in Australia. You will not find them in Lebanon or Jordan or in any other country of origin.

I wrote The Lebs to shed light on the psychological effects of racism on those young people and how they either adapt to their way they’re presented in the media or hate themselves.

After 9 /11 and other incidents in Australia — the gang rape in 2000 and the riot in 2005 — the young Lebanese were treated differently and were represented in the media as violent people and terrorists. It was hard for young people to avoid seeing that.

The Lebs talks about violence in a school and how sometimes those young people act out because they have encountered racism, so they pretend to have guns, to be strong and part of gangs. They are trying to protect themselves from what they are facing in the community.

HS: You named your character Bani Adam – means the son of Adam.

MMA: Bani Adam in Arabic means a human or a person. He represents humanity.

Bani Adam didn’t love himself as an Arab, and he thinks he is better than the others. He didn’t want to relate to any Arab. But in the end he learned to love himself and to be an Arab.

‘Bani Adam thinks he’s better than us!’ they say over and over until finally I shout back, ‘Shut up, I have something to say!’

They all go quiet and wait for me to explain myself, redeem myself, pull my shirt out, rejoin the pack. I hold their anticipation for three seconds, and then, while they’re all ablaze, I say out loud, ‘I do think I’m better.’

It’s hard for the young people from minority communities to know how to love themselves in a climate that hates them.

In The Lebs, I wanted to tell the world that, regardless of our beliefs and our cultures and languages, we are all human in the end, and we all face the same life.

Talking about racism, I would like to mention something Ghassan al-Hajj had said: The young generation faces racism twice as bad as the generation before them. It’s harder for them, because the racisms come from their own people in their own language — those people who are born on this land — who are Australian and speak English, and they don’t know the country of their parents.

HS: How do you see the Arab Australian literary scene? Are Arab voices heard?

MMA: All minority groups in Australia are under-represented on the literary scene, not only the Arab Australian.

The system only supports White writers, and publishers doesn’t understand different cultures and don’t try to. Even schools and universities teach only European and Anglo-Australian literature.

But change is happening.

Hend Saeed loves books and has a special interest in Arabic literature. She had published a collection of short stories and recently started “Arabic Literature in English – Australia.” She is also a translatore, life consultant, and book reviewer.

Michael Mohammed Ahmad’s ‘The Lebs’: Depicting Arab Lives in Australia – Arabic Literature in English (Australia)

February 27, 2018 @ 3:10 am

[…] Michael Mohammed Ahmad’s ‘The Lebs’: Depicting Arab Lives in Australia […]