‘The Responsibility of Translating Other Poets’

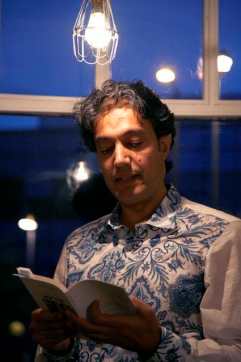

A wide-ranging talk with London-based Iraqi poet-translator Ghareeb Iskander:

By Hend Saeed

Iraqi poet and writer Ghareeb Iskander was born in Baghdad in 1966 and has been living in London since 2002. He’s published a numerous of poetry collections, including High Darkness (Sawad Basiq 2001) and A Chariot of Illusion (Mahafat Alwahm 2009). In 2012, Syracuse University Press brought out a bilingual English-Arabic collection of his works, called Gilgamesh’s Snake and Other Poems, co-translated by Iskander and John Glenday. This collection was winner of the University of Arkansas Translation Award.

Iskander himself is also a translator, working between Arabic and English.

Iskander himself is also a translator, working between Arabic and English.

My favorite part from Gilgamesh’s Snake:

Uruk is an empty ruin,

all its people fled.

Such devastation; the streets

shimmer in a caul of silence.

He wanders alone—

not a single tree shades his scorched soul,

no wine to quench his longing.

All alone, he cries,

and because victory for him is a defeat that never ends

till the ends of his life, he must

ride the magic palm frond.

After reading Gilgamesh’s Snake, I followed Iskander and wanted to know more about his work, what he thinks about 2018 Baghdad Book Fair, and the Baghdad publishing scene.

HS: What are you working on now? Anything coming soon?

GI: I am currently working on a new collection of poetry, though I’m not sure yet exactly what it will be. Some of the poems were written when I was in Brazil, some in Beirut, and some in London.

I am also working with the Scottish poet John Glenday on translating selected poems by the Iraqi poet Ḥasab al-Shaik Ja‘far. This is our second project together. The first was a translation of my book Gilgamesh’s Snake and Other Poems, which was published in 2016 by Syracuse University Press.

When translating from Arabic into English I normally work with a native-speaker poet; when translating from English into Arabic I work alone, such as for Hunā Yakmun al-Furāgh (Here is the Emptiness), the selected poems by Nobel laureate Derek Walcott, which was published in 2015.

HS: What did you think of the 2018 Baghdad Book Fair? Was it a good sign?

GI: I have been back to Baghdad many times since the Change of 2003, but my visits never coincided with the Baghdad Book Fair, except in 2012. Book fairs are always a sign of a country’s healthy literary environment, as they are a chance for writers and readers to meet and discuss their works and other writers’ books, but for a country like Iraq, which has undergone turbulent upheavals in recent times, this is especially true.

Exiled writers who went abroad many years or even decades ago are now able to attend, as are Arab writers from other countries. Often this represents the first opportunity many readers have to meet their favorite writers face to face. The 2018 Book Fair was especially important because it came after the liberation of Mosul and other cities from ISIS. Books and culture can help rebuild what has been destroyed by terrorists. Book fairs can help schools, universities, and public libraries to rebuild their collections. These are all good signs about the ongoing rebirth of Iraq’s literary environment.

HS: Along with the Baghdad Book Fair, the literary and publishing scene in Baghdad is changing. What do you think about these changes?

GI: One clear change since 2003 has been in the themes taken up by Iraqi poets and novelists and, indeed, by artists generally. Perhaps not surprisingly, much of this has dealt with first hand experiences of war and terrorism, but there has also been a blossoming of a wider range of voices and political opinions. This is not to say that there is not scope for further opening of cultural, religious, and gender issues.

GI: One clear change since 2003 has been in the themes taken up by Iraqi poets and novelists and, indeed, by artists generally. Perhaps not surprisingly, much of this has dealt with first hand experiences of war and terrorism, but there has also been a blossoming of a wider range of voices and political opinions. This is not to say that there is not scope for further opening of cultural, religious, and gender issues.

On the matter of poetic form, there has been less radical change than that which occurred with the free-verse movement established in the aftermath of WW2 and the loss of Palestine. At that time, Iraqi poets and those of other Arab countries felt that the classical form restricted their handling of these themes and so searched for a new and flexible form.

The multi-stanza form of “The Waste Land” and its complex themes, for example, influenced the Arab poets in the 1940s and the 1950s to use this technique in their poems. They felt this new poetic form was able to cover all social and political problems that arose as a result of WW2. This was clearly reflected in al-Sayyāb’s poems, especially his masterpiece “Unshūdat al-Maṭar” (“Rain Song”). Arab modernists adapted the Western poetic techniques, however, to create an organic response to Arabic poetic traditions.

Although these techniques — in particular the prose poem which dominates Arabic poetics at present, seem capable of expressing and exploring these ‘catastrophic’ issues of invasion and occupation, terrorism, corruption and the heritage of dictatorship in Iraq after 2003 — it will be interesting to see if a new aesthetic treatment evolves over coming years.

Translations might play a crucial role in this process, as it did in establishing the free verse and, subsequently, prose poem movements. This is not to diminish the creative contribution of these poets, however, since most movements and schools in the history of world poetry have depended heavily on translation of and influence by those of other cultures.

Poets have always undertaken the responsibility of translating other poets. Thus, in modern time, many Western poets were also translators, such as Pound, Eliot, Baudelaire, St.-John Perse, Rilke, Auden, and Stephen Spender. Likewise, almost all Arab modernists were translators: Sayyāb, Nāzik al-Malā’ika, Adūnīs, Yūsuf al-Khāl, Tawfīq Ṣāyigh, Buland al-Ḥaydarī Jabrā Ibrāhīm Jabrā, Sa‘dī Yūsuf, Lūwīs ‘Awaḍ and Ṣalāḥ ‘Abd al-Ṣabūr. It is against this background that I too have started to translate those poets I feel worthy introduction to Arabic readers and to a lesser extent vice versa.

HS: How can we do a better job of supporting poetry, when so much support goes to the novel?

GI: This is a difficult but important question. Poetry is a dominant literary genre in many countries, especially in Iraq and other Arab countries. It’s often considered the highest representative art and is used widely in education. Poets are viewed as generous and humanistic, are often called on to contribute their creativity to aid others in times of crisis, such as to raise funds and offer spiritual and mental support for peoples affected by war or natural disaster. Yet they get relatively little support from governments, institutions art councils etc., compared to other literary genres. How this can be changed … I wish I knew.

HS: What are the new exciting things you think is happening in poetry?

GI: Poets and poetry lovers across the world organize festivals, workshops, translation events, and creative meetings. They invite other poets to discuss and translate their poems to broaden their audiences. This is perhaps the most exciting thing as it brings writers and translators together despite their different backgrounds, languages and cultures. On a personal level I am particularly moved when I meet poets from the Middle East or other war-torn areas for whom poetry is a powerful device that enables them to deal with the misfortunes they have encountered.

Read more poems by Iskander in translation.

Hend Saeed loves books and has a special interest in Arabic literature. She had published a collection of short stories and recently started “Arabic Literature in English – Australia.” She is also a translator, life consultant, and book reviewer.

‘The Responsibility of Translating Other Poets’ – Arabic Literature & Culture in English (Australia)

July 30, 2018 @ 1:46 am

[…] ‘The Responsibility of Translating Other Poets’ […]