Tawfiq al-Hakim Day: Genius, Humorist, Misogynist, Grouch

The great Egyptian writer Tawfiq al-Hakim was born on this day in Alexandria in 1898:

Al-Hakim began his life in Alexandria — the son of an Egyptian judge and a Turkish belle — before moving to Cairo for secondary school. When his parents discovered his passion for the arts, they packed him off to Paris with the misguided hope it would turn him to practical things, in particular life as a lawyer. But when he returned to Egypt at the age of 30, al-Hakim was bristling with ideas for a new Egyptian theatre. His seminal People of the Cave was staged five years later, the inaugural play of the Egyptian National Theatre Troupe.

Al-Hakim is remembered as a playwright — and it’s generally agreed that’s where he had the most impact — but he also wrote essays, memoir, short stories, and daring novels.

Genius

People of the Cave, Fate of a Cockroach (translated by Denys Johnson-Davies), Return of the Spirit (translated by William Maynard Hutchins)

People of the Cave, Fate of a Cockroach (translated by Denys Johnson-Davies), Return of the Spirit (translated by William Maynard Hutchins)

Naguib Mahfouz wrote, in a section of his memoirs translated by Hala Halim, on Tawfik al-Hakim’s pioneering theatre work in (People of the Cave) and his novels, (particularly Return of the Spirit). He also managed to work in some shade, here, for Mohamed Hussein Heikal, because why not:

The first work I read by Al-Hakim was Ahl Al-Kahf. But of all his works it was the novel ‘Awdat Al-Ruh which had the greatest impact on me, for I had never before read a novel of such beauty, elegance and ease. But when I became more mature I realised that Al-Hakim’s true accomplishment was as a playwright rather than as a novelist, and that ‘Awdat Al-Ruh is nothing but a play written in narrative style, but basically consisting of dialogue and stage settings. Indeed, ‘Awdat Al-Ruh influenced my fiction writing as much as the works of El-Mazni and Taha Hussein. The influence of ‘Awdat al-Rawh on me went way beyond that of Dr Mohamed Hussein Heikal’s novel Zeinab which barely left any effect on me; in fact I think I forgot all about it as soon as I put it down.

You can read an excerpt of Return of the Spirit online.

Al-Hakim also apparently was a genius at self-promotion. As Mahfouz wrote, tr. Hala Halim: “Later I discovered that it was Al-Hakim’s custom, dating all the way back to Ahl Al-Kahf, to intimate to whoever he showed a manuscript of his how secret and dangerous it was in order to draw attention to the work.”

Humorist

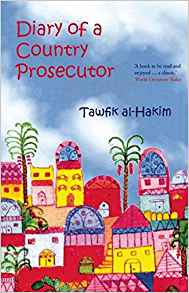

Diary of a Country Prosecutor, translated by Abba Eban;The Prison of Life, translated by Pierre Cachia (excerpted in The Essential Tawfiq al-Hakim); Tawfiq al-Hakim’s Secrets of a Suicide, translated by Maha Swelem.

Diary of a Country Prosecutor, translated by Abba Eban;The Prison of Life, translated by Pierre Cachia (excerpted in The Essential Tawfiq al-Hakim); Tawfiq al-Hakim’s Secrets of a Suicide, translated by Maha Swelem.

My favorite al-Hakim is probably the funny al-Hakim, although usually the tragi-funny al-Hakim.

Diary of a Country Prosecutor is a serious comedy of errors. It presents as the purported journal of a young public prosecutor — full of European “enlightenment” ideals — who is posted to a rural Egyptian village. What ensues is a clash between the prosecutor, this bearer of the “enlightened” colonial legal system, and the “unenlightened” people of the Egyptian village.

You can also watch the film based on this novel online.

More humor: In his memoir The Prison of Life, al-Hakim often writes with sardonic, sometimes tender exasperation about his father, and especially his father’s building projects. And while al-Hakim considered his play “Secrets of a Suicide” to be a comedy, translator Maha Swelem believes it to be more properly a tragicomedy. Act I opens:

Mahmoud: Salem!… close the doors and do not open to anyone whomsoever…

Salem: And if that young lady came…

Mahmoud: If that young lady came… do not open! … Understood?

Salem: What about the patients?

Mahmoud: Sick or healthy, all the same…. Understood?…

Salem: Understood… ( under his breath ) I can’t get it…

You can keep reading at ArabStages.

Misogynist

The Sacred Bond (Al-Ribat al-Muqaddas).

The Sacred Bond (Al-Ribat al-Muqaddas).

Al-Hakim was a self-confessed anti-feminist, and this, too, was a part of his literary project. Unsurprisingly, his seminal “women are dangerous, look out!” novel has not yet been translated into English.

Denis Hoppe wrote hilariously of the 1945 novel in his 1969 bachelor’s thesis: “Although he [al-Hakim] has married, and forgiven women some of their faults, he was always anti-feminine. He feels that a woman is the flower of the arts, culture and society, but that like some flowers she has thorns with which she ensnares man and causes unspeakable trouble.”

Further:

…it is hard to understand why this thoughtful man, who would never write without reason, should write a book like al-Ribat al-Muqaddas, which only reinforces old bigoted beliefs. Is there something more important he is trying to say? Is he trying to warn his people, through exaggeration, that Egyptian women are evolving too quickly; becoming Western in their dress and lipstick, but not really overcoming their basic instincts?

Maybe, maybe.

Grouch

The Revolt of the Young: Essays by Tawfiq al-Hakim, translated by Mona Radwan

The Revolt of the Young: Essays by Tawfiq al-Hakim, translated by Mona Radwan

The Revolt of the Young, published in Arabic in 1984, collects some of the author’s “nonliterary” essays. Published just three years before al-Hakim’s death, it is written mostly in a loquacious newspaper style. It sometimes takes the “when I was a boy” tone of a writer near the end of his days, a grumpy old man ranting about unisex bathrooms.

In one essay, Al-Hakim remembers:

It was on a day in 1935, when I was the director of investigations in the Ministry of Education as well as a well-known writer, that my father paid me a visit in my office. A reporter was interviewing me concerning literature and art. I was taken aback when my father interfered in my interview, wanting to direct it the way he pleased, correcting my opinions in keeping with his own views and beliefs.

But more than four decades later, the grouchily self-aware al-Hakim finds he is not altogether different from his father. He scorns his son’s work as a jazz musician — after all, this is not proper (European) classical music — and is bossy, imperious, uninterested in his son’s concerts. Finally, Yusuf Idris and some other friends coax al-Hakim into attending one of his son’s concerts. The grouchy old Al-Hakim enjoys himself, a bit, but he’s still awkward and out of place (“like a rustic in a Moulid”), and later he’s embarrassed at the idea of joining the young people. “For a father like me, the feeling of anxiety is greater than that of satisfaction.”

Al-Hakim was a pioneer in a number of stylistic and formal ways. But it was often enough his irritable awareness of his shortcomings that made him a witty, enjoyable writer.