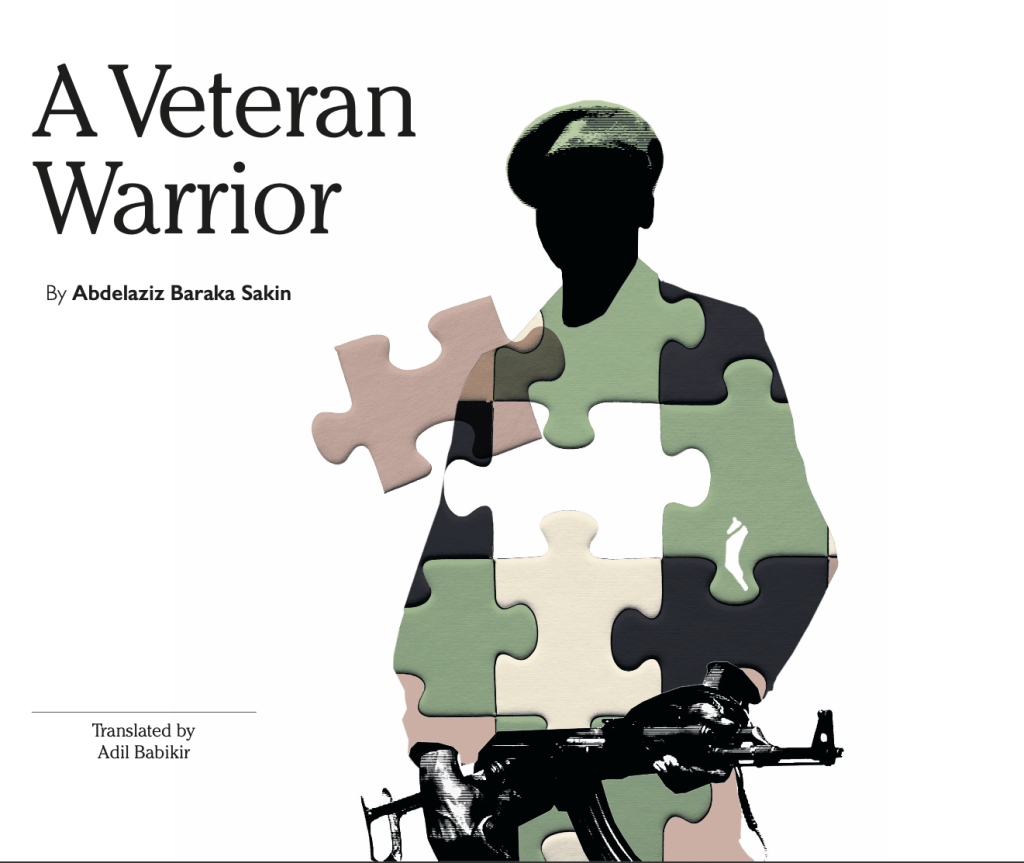

Fiction from Sudan: Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin’s ‘A Veteran Warrior’

This short story, by the celebrated Sudanese novelist and short-story writer Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin, originally appeared in our CRIME issue in the Summer of 2020:

A Veteran Warrior

By Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin

Translated by Adil Babikir

“Will they shoot again?” the little girl asks her mother.

“No.”

“But you said they were drunk, Mama…”

“The same alcohol that made them want to shoot will soon put them to sleep, and then they’ll stop.”

Although not wholly convinced, the little girl falls asleep while her mother is kept awake by the vision of a drunken soldier storming in at any moment, a random bullet striking her sleeping child or herself.

No one can stop drunken soldiers from firing just as no one can stop them from drinking. Even the authorities don’t do anything.

“When an armed, drunken soldier is provoked, he can kill anyone—even his partner or his wife,” her husband had once jeered, mocking his wife and daughter as usual. “He might hurt you and Intisar. Hurting or killing you isn’t a threat to national security.”

Her husband, a driver for a private company, was on a work assignment outside the capital tonight.

They were going to fire again. She’s quite sure. “Tomorrow I’m going to move from this damned place to my father’s house. When Sabir is back, I’ll tell him it’s either me or this damned house.”

There’s another knock on the door. Her hand stretches out unconsciously and switches off the main light, leaving only a small lamp on. She presses the child to her chest and closes her eyes, while her ears remain alert to the sounds drifting in from outside. Her husband wouldn’t knock; he has his own key. And she doesn’t expect visitors at this time of night. More persistent knocks. She shuts her eyes tighter and tighter. Tomorrow she’ll leave this godforsaken place. The knocks on the outer door are getting even louder. The little girl wakes up.

“Why didn’t you go to sleep, Mama? Are they going to shoot again?”

They call themselves “owls” because people think the sound of an owl is an evil omen and that, if an owl enters their house, one of them will surely die. People also believe that anyone who sees an owl during the day will lose their eyesight, and if they see them at night, a man will lose his virility, a woman her fertility.

The little girl’s father calls them “the night devils,” her mother refers to them as “the gang,” while the authorities describe them as “the fearless soldiers standing against the forces of infidelity and aggression.” The little girl is desperate to sleep; she thinks of them as “the war people.”

The knocks are now more frequent. The little girl closes her eyes. The mother closes her large eyes.

“Could it be dad?”

“Your dad has a key.”

“It could be my uncle coming back from one of his trips.”

“Your uncle isn’t due back yet.”

“Then let me attack them, Mama. They’re the enemies.”

“Go to sleep, darling. The door’s locked. They can’t come in. We don’t need to attack anyone.”

The little girl closes her mouth with her amputated hand. Intisar enjoys playing with Mustafa, their young next-door neighbor. Mustafa likes playing “army versus army.” She plays the game, too, and together they took part in the major assault against the creek revolts, the battle during which she lost her right hand, when both Saleh and Siddig died, and the hero Asmaa lost an eye. That was exactly a year ago.

“I’m not drunk. I’m not a burglar.”

“Is he an enemy, Mama?” asks the little girl.

“Go to sleep, darling.”

“Are you going to switch off the lamp, Mama?”

“Leave it on. Don’t worry about anything. You need to get up early tomorrow for school.”

“Have they got bombs like the ones we found in the big creek?”

“They’re drunk. They can only carry light weapons.”

“If Mustafa was awake, he wouldn’t have let them do this.”

Her mother smiles bitterly, stirred by the painful memory of the amputated hand. No one can do anything to protect the children. There are weapons everywhere: at the river, the creek, the nearby farms, the bush, beneath the walls of the houses. Bombs, mines, hand grenades, ammunition…

It seems the neighbors have come out and are hounding the night visitor with questions. There are lots of them. Now it’s the neighbors who are knocking. She can hear Aunt Nafeesa say: “What happened to Amna and her daughter?”

“That’s Auntie Nafeesa; has she joined the enemies, too?”

“We’re not opening the door to anyone.”

*

The shooting starts again, heavier this time. Maybe some heavy arms are being used. The knocking stops. They might have laid down flat to take shelter behind rocks or bushes in the moonlit night. No one can see them. They were drinking somewhere nearby. They’re reckless. They respect no one and fear no one—they call themselves “the owls.”

I know my mother is afraid because she never took part in a battle before. She didn’t take part in the big assault on the creek revolts. She wasn’t trained by Mustafa. All she can do is close her eyes.

*

The shooting starts up again. It’s sporadic. My daughter goes to the bathroom: a small, roofless structure at the back of the house, the side next to our neighbors. I follow and wait outside for her to finish so I can go in to help her wash; she can’t do it by herself with the one hand. But she isn’t coming out. She’s taking too long.

The minute I call out, her voice comes to me from the direction of the outer door, yelling:

“Everyone freeeeze! Or I shoot.”

*

Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin is one of the most prominent novelists and short story writers in Sudan, with more than 15 works of fiction to his name. These include novels such as The Jungo: Stakes of the Earth, The Messiah of Darfur, The Bedouin Lover, The Khandarees, and Samahin. His short story collections include At the Peripheries of Sidewalks, A Woman from Kambo Kadees, and Bones Music. Sakin now lives in Austria and writes for a number of prominent Arab literary publications.

Adil Babikir is a Sudanese translator and copywriter based in the UAE. His translations include Mansi: a Rare Man in His Own Way by Tayeb Salih (Banipal Publishing, 2020); Modern Sudanese Poetry: an Anthology (University of Nebraska Press, 2019); The Jungo: Stakes of the Earth, by Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin (Africa World Press, 2015); Literary Sudans: an Anthology of Literature from Sudan and South Sudan (Red Sea Press, 2016). His unpublished works include the Messiah of Darfur by Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin, an anthology of short stories, and a book on Sudanese folk poetry.

*

Read more:

Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin’s ‘Les Jango’ Wins Le Prix de la Littérature Arabe 2020

Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin Wins ‘Committed Book Prize’ for Novel Seized at Recent Khartoum Book Fair

An Ever-so-short History of the ‘Complex, Capacious’ Sudanese Short Story

10 Sudanese & South Sudanese Short Stories for the Solstice