Jonathan Smolin on the Relationship Between Ihsan Abdel Kouddous’s Politics and His Novels

By M Lynx Qualey

Jonathan Smolin is not just the translator of Ihsan Abdel Kouddous’s I Do Not Sleep, newly published by Hoopoe Fiction. He also recently finished writing a scholarly book about Abdel Kouddous, and his translation of a second novel of Abdel Kouddous’s, A Nose and Three Eyes, is forthcoming.

For this special section, he talked about Ihsan’s relationship with his publisher-mother, with Gamal Abdel Nasser, and why I Do Not Sleep was really about an analysis of the political events in Egypt in 1952.

When and how did you first come across Ihsan Abdel Kouddous’s writing?

Jonathan Smolin: Many years ago, when I was learning to read Arabic literature at the University of Chicago back in the mid to late 90s, I had an Egyptian Arabic professor who was also a translator, Farouk Mustafa (he translated under the pen name Farouk Abdel Wahhab), and we learned how to read—we learned how to turn pages—by reading Ihsan. We read so many of his short stories, and they’re just perfect for that bridge to turning pages instead of deciphering paragraphs.

I remember at the time that Farouk would say, “It’s disgraceful that no one’s taken him seriously as a writer, and it’s awful that nothing of his stuff has been translated! And he’s one of the most important writers in Egypt and he’s completely ignored by the critics!” And I remember thinking at the time, Maybe I’ll do a project on that someday.

After tenure, I decided I wanted to do something new and something different. I would say I started this project in earnest in 2018.

In 2018, I went back and said, Well, surely someone in the last 20 years has translated Ihsan, and surely someone has written seriously about him, and no one had, so, I went and re-read or read all of his fiction, and I realized that he was such a force of journalism, and that everything he wrote was serialized either in Rose al-Yusuf or Sabah al-Khair, I realized that all of these magazines had editorials by him, about politics and culture and society, and that he wrote under a weekly deadline.

He was not Mahfouz; he did not write the entire novel and then serialize it. He wrote on a weekly deadline. Whenever the magazine was finished for that week, he would close the office door and write the week’s chapter, and when he walked out of the office, that was it. It’s easy to overlook this when you read them as books, but all of the chapters are the same length because they were all serialized in the magazine under a word count. And many of them end with cliffhangers.

So in 2018 I began reading and re-reading all of his fiction, which was a lot, and then going back and pairing the fiction—when it was serialized—with the editorials that came along with each of the chapters. That’s when I realized how intensely political his fiction was, and that it had been read as “the first Arab novelist who took the perspective of women seriously” and as an advocate of women’s rights, and he was, but there was also an intensely political subtext to his fiction that has been forgotten because—people who read him outside of the generation of the 1950s and 1960s—knew him through reading his books, or seeing his movies. But they didn’t know him in his original context, which was week in, week out, publishing alongside an editorial.

And you can see strong links between the editorial and the chapter of the novel by pairing them together. That really launched me onto the book project that I’m wrapping up.

But the reputation of La Anam is that it’s not one of his political books.

JS: Oh, it’s so political! It’s about the coup!

In very simple terms, Ihsan participated in the coup. He was called to the barracks by Nasser the morning of the coup. And Ihsan felt a deep sense of responsibility for the revolution. He had written many editorials calling for revolution before July 1952; he was the one who broke and spread the story of the rotten weapons. Do you know this story?

Unfortunately, no.

JS: This is very important to understand: He was collaborating with the free officers before the coup, in 1950, 51, and 52, to basically prepare public opinion for the coup. So this was the story that the king had bought an enormous amount of defective weapons at inflated prices, but that they were all faulty. Hand grenades blew up when people touched them, rifles shot in reverse, and Ihsan was the one who spread this scandal in Rose al-Yusuf with leaked documents from the Free Officers.

Ihsan really felt this strong sense of responsibility for the revolution, but like a lot of intellectuals after 1952, he felt like he could control the Free Officers, as he felt he had done before the revolution, and the officers turned against him, like they did with other journalists and other intellectuals. And they jailed him, and they abused him. So what La Anam (I Do Not Sleep) is really about is the girl who orchestrates a coup in her own home to expel the British-seeming stepmother and then brings into the home the traitor.

It’s his own confession of the way that he had orchestrated this coup, in his own house—and it doesn’t take a large imagination to think of the household as the nation—and bringing in the traitor that he personally knows, where he’s the female character. He knows that she’s the traitor, but he can’t tell anyone.

Nadia can’t reveal this to the father—the symbol of Egypt, happy with the traitor and is blindly in love with her. It’s shocking to me that no one saw that by reading that book. But much of his fiction is his confessional experience of his own regrets and what he had done by abetting someone who he came to see as a traitor to the nation. And he does this again and again and again in his fiction.

Why do you feel people haven’t read it as a political novel?

JS; I think what happened was that the novels got sanitized as films. The ending of the film is radically different from the ending of the novel. In the film, Nadia is punished. She’s literally burned. She confesses and apologizes, and the traitor is expelled from the house. But in the novel, she’s left in depression in her bedroom, and the traitor is permanently embedded in the household.

I think one thing that has been a tremendous disservice to Ihsan is that so many of his novels were turned into classics of melodrama in Egyptian cinema, and people think that the novels were the films, and the endings were almost inevitably radically transformed to suppress the dissent that Ihsan was trying to articulate.

Now, I find it hard to believe that his peers didn’t read it like that, but it just was dangerous to point it out. They knew, but I just think no one was commenting on it.

Why is this more the case for Ihsan than for Mahfouz, whose novels were also made into films?

JS: I’m speculating here, but I don’t think Mahfouz’s films were as popular as Ihsan’s. If you think about it, there were so many classics of melodrama, and so many actors and actresses really built their careers on his films. Fifty films were based on Ihsan’s fiction.

Also readers, I think, took Mahfouz more seriously. I think people saw Ihsan as diversion and entertainment as opposed to high literature.

There are so many people I’ve talked to during this project who assume that the endings of the novel were the endings of the films.

They remain popular, including in illegal downloads of 4shared and elsewhere. Do we know the circulation of his work in serialization?

JS: I’m not sure anyone knows the numbers, but Rose al-Yusuf was definitely the highest circulation magazine. And then he became the editor-in-chief of Akhbar al-Youm, in 1965, and that reportedly immediately shot up to over one million circulation, and that’s a weekly. We presume that Rose al-Yusuf was under a million, since it was so striking that Akhbar al-Youm was over a million.

But he had a magic touch with the press. He was a tremendous populist, in that sense. He made fun of Mahfouz and Taha Hussain for their elevated style in his editorials, at times. He worked very hard to popularize his language, his style. And there’s tremendous interplay between the style of the editorials and the style of the fiction. And so he really recognized the importance of sales and circulation. They didn’t make a lot of advertising, so it was critically important that people came back each week for the new installment.

Raph Cormack’s Midnight in Cairo was released last year, and among other people it profiles is Ihsan Abdel Kouddous’s mother, Rose al-Yusuf. To what extent did his mother, and the milieu he was raised in, shape his fiction and his journalism?

JS: He clearly had a very complex relationship with his mother. His parents divorced when he was very young. He was given to his father’s family to be raised, and his mother was seen as a kind of social pariah because she was an actress, and they wouldn’t let her into the house. She would come once a week, and he could only see her outside of the house, and then eventually, when he was a teenager, I think he started living with her part-time.

In interviews late in his life, he talked about the way that he grew up in two radically different milieus: the milieu of his father’s father, which was religious, conservative, and strict, and tradition, and then there was the milieu of his mother. And at her apartment, he met all of the poets, and the politicians, and the kind of life that you read about in Midnight in Cairo, although I’m sure she didn’t let him see everything. But he still met the liberal intelligentsia of the 1930s, whereas at his grandfather’s house, it was very strict and conservative.

And this was something that clearly stayed with him throughout his life. He enjoyed life, he always had lovers, and he didn’t hide it.

You open your introduction with a thunderclap, “It is shocking that Ihsan Abdel Kouddous is still largely unknown outside of the Arab world.” Why do you say it’s shocking that Ihsan isn’t better known and regarded? Why do you think he and his work should be better known?

JS: Think of how many different marginal writers are translated, whereas Ihsan is perhaps the most prolific and most popular writer of Arabic in the twentieth century. What is it that pushes a press to publish a novelist in translation? Is it their reception in their original context? Is it their appeal to others in the translation’s language? Frankly, the fact that he was so prolific and so popular for so long tells us something extremely important about the kind of literature that’s appealing in Arabic, and that has been appealing to audiences through generations.

The AUC did a poll in 1954, and he was already the most popular author in Egypt in 1954, and that was before he did all his huge classics in the 1950s and 1960s, it was only after one or two important novels at that point. I think the reception in Egypt in and of itself is very, very important. Another part is that you cannot understand the trajectory of modern Arabic literature without reading him. There has been a tremendous bias to high literature in translation. He is someone that is of massive importance in the development of the novel in the twentieth century. Just because the leftist critics didn’t like him doesn’t mean that he didn’t play an important role.

I think that his neglect shows the unfair influence of a particular perspective on what the Arabic novel is, within the translation industry.

Why is it interesting now, for someone to read in English, and what type of reader do you imagine for the translation?

JS: I think that there’s an interest in the 1950s, and this is a perspective that’s been completely overlooked in the Arabic literature that’s been available in translation.

But I think there’s another point here that’s important, and that’s that he was just a good storyteller, and I think that gets overlooked. In some ways, the literature of the Arab world has become synonymous with a kind of political reading, and it’s absolutely true that this novel is heavily political, but Ihsan thrived because he was able to express what he wanted to say politically in ways that were diversionary, in ways that were exciting and readable and fun and interesting, and that attracted wide audiences.

And this book, La Anam, was his first real mega-hit. It was the one that really attracted a huge audience and captivated readers. Every issue of Rose al-Yusuf had these fascinated reader letters and reader responses. The Emir of Kuwait wrote in.

Why read this today? I think it’s a critical part of Arabic literary history, a window onto a very important and influential period that is underrepresented in translation, and I think it helps us rethink what popular culture was in the 1950s. It’s also a refreshing reminder of Egypt in the 1950s and really how radically different that is from today—and it’s just a great story.

Does this mark a different period in his writing?

JS: Yes. So he was jailed in from April to late July in 1954, and he wrote two quick novels when he got out of jail in August of ‘54.

Two quick novels when he got out of jail!

JS: He could just write. One was really a bizarre book, where he’s coming to grips with what it meant to be jailed. And then he wrote another long novel after that, that really expressed his regrets about participating in the coup. And then he wrote editorials about suffering from insomnia right around the time he was preparing this novel.

It was immediately after this period of trying to reconcile himself with the fact that Nasser is here to stay, and Ihsan’s revolution—how he imagined it—is gone. He had kind of recognized that who he saw as the traitor was permanently embedded. After this, he turned to fiction to express his regret and anxiety, and he abandoned the editorial as that space. Before his jailing, the editorial was the space to protest. It was after the jailing that the fiction became the space of protest, and the editorial became the space of necessary propaganda. He had to write about Nasser in the glowing terms that everybody else did.

And how did Nasser feel about Ihsan’s books?

JS: Nasser loved reading Ihsan. Nasser did not read books, but Nasser read magazines, and this was a big difference of why Nasser read Ihsan and really didn’t read other novels, because Ihsan was serialized in the most important weekly.

Ihsan used these novels to protest to Nasser directly. There are things in them that really only Nasser would have understood. There are times when he gets in trouble, and it’s directly related to the way that he inserts Nasser as a character into his fiction. This is a big problem in his novel Al-Banat wa al-Saif, Girls of the Summer.

It’s a big shift in terms of his popularity, as well as his productivity. When one ends, he begins the next. And in between, he’s writing short stories all the time. But the prolific writing, I think, reflects a kind of therapy, a self-therapy, a way of trying to come to grips with—what he thought he was doing was liberating Egypt, but what it turned it into was a military dictatorship. And he never worked through his own regret, he never got over it.

I think that the fiction from this period, from La Anam (1956) to A Nose and Three Eyes (1964), is an attempt to work through his sense of regret and anxiety.

So maybe the people who believed the character Nadia Lutfi was real—as you talk about in your introduction to the novel—were correct?

JS: Yes! And it was him! People ask, “How could Ihsan feel women that way?” And I think it’s funny when I hear it, because he wrote himself as the woman. He is always the female character, with few exceptions.

I think it didn’t occur to people in the 1950s that he was putting himself in the position of the female protagonist. In about 1955, Mahfouz just mentioned offhand in some interview that of course Ihsan was the narrator of I Am Free. And Ihsan was outraged, and he wrote this editorial insulting Mahfouz, and then a few weeks later, he said: Of course he’s right.

Can you talk about their relationship? Naguib Mahfouz and Ihsan Abdel Kouddous?

JS: They grew up in the same neighborhood, Mahfouz was older, so it wasn’t like they were direct peers, but they went to the same high school, and they remained close throughout their careers. Mahfouz wrote the screenplays for a couple of Ihsan’s films, and he added an extra critique in them that the other films lack.

They were very, very close. There’s an incredibly video of Ihsan going to congratulate Mahfouz when he won the Nobel Prize, and you can see how really touched Mahfouz was. There was some tension. No doubt Mahfouz didn’t appreciate him making fun of his high literary language from time to time, but they were close.

So there was not a gigantic divide between the men of high literature and the men of popular literature.

JS: I’m sure Mahfouz thought Abdel Kouddous was a populist, because his language is really simple and it’s intentionally so to sell magazines. He wanted people who were not literary to read his work, and for that reason he had a much wider impact than someone like Mahfouz in the 1960s and 70s.

Many contemporary writers talk about being influenced by Naguib Mahfouz, and many books have clear intertextual references to Mahfouz’s novels; it’s less common to hear someone saying they were influenced by Abdel Kouddous. Where do you see his influence?

JS: Ihsan was heavily influenced by the populist writers of the 30s and 40s in the press. He also read widely in English, and he read international writers. He didn’t read French, but he was very influenced by French writers, and by Italian writers. And La Anam was very loosely based on a French novel by Françoise Sagan.

I think, in some ways, he’d be a godfather of the popular literature of the past twenty years in Egypt. When you think about the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, much of literature was more influenced by Mahfouz than by Ihsan.

Maybe Ahmed Khaled Tawfik?

JS: Right, that’s what I mean, the populists of the late 90s up until today. Ahmed Khaled Tawfik, Alaa al-Aswany.

I originally thought I was going to write a book about Egyptian dystopia, because there was so much of it in 2016, 2017. And I was talking with Ahmed Khaled Tawfik about this, and he said, No no no, write the book about Ihsan.

And as a translator of Ihsan’s work—what were the main things you wanted to carry across?

JS: Flow. I am not the dissidence translator. I want to hide; I want to be absent. I don’t want people to think of me. I want it to be accurate, but also to do everything possible to duplicate the experience of reading Ihsan in English without me around. That’s my goal.

What was funny for me was that, when I got the first edit back, they had changed things around and inserted a number of semi-colons. And I really insisted: Ihsan would never have used a semi-colon.

I worked on this translation a lot, and I feel like I did the best honor to Ihsan that I possibly could.

Do you imagine teaching this? What sort of material would you work around it?

JS: I teach several different courses that I could teach this in. One is, I teach a survey of modern Arabic literature, and the thing that always frustrates me about teaching this class is that I’m always waiting until literature 2000 to include popular literature. Because we don’t have popular literature in translation from the 50s and 60s. So this fills a critical gap for me in that kind of syllabus coverage.

Another course I plan to develop is 1950s Egypt, now we really do have a lot more material. We could call it Nasser and Popular Culture or Nasser and Culture, and really do an interdisciplinary course, with not just fiction, but film, and spend some time one summer and translate a bunch of editorials, and look at the politics of the United Arab Republic. I think this book would fit very, very nicely. I think the book would also fit very nicely in the relationship between the intellectual and the state, because this book is a book of protest.

I also teach a course called Introduction to Middle Eastern Studies, and that’s a broad survey course, and I could use this as an example of the relationship between fiction and the state, and teach it as an allegory of the coup.

Did Ihsan ever write any kind of memoir?

JS: He said again and again and again that all of my memories of the politics are in my fiction. He was quite explicit about that. He gave several series series of interviews in the 70s and 80s, when he talked about aspects of the build-up to the coup, the participation in it, his jailing, his relationship with Nasser, but Nasser haunted him. And unlike some other figures, he was really careful not to be too explicit about his relationship with Nasser. He had a complex relationship with Nasser.

There are so many biographies of Mahfouz, where are the popular and scholarly works about Ihsan?

JS: Again, that’s what my book is. And what you do have is a number of books of interviews, and biographies that just look at his journalism, and look at him as the editor of Rose al-Yusuf.

When people talk about Ihan’s fiction they talk about him as the writer of love. For these people, he was a radical in terms of his editorial, but he was the writer of love in his fiction. And this idea has spread among writers that he was political when he wrote his editorials, and he was completely apolitical when he wrote his fiction.

And Ihsan said again and again in his editorials: I’m political when I write fiction, and I’m a fiction writer when I write editorials. The editorials, after 1954, were this obligation to praise Nasser because he had to, but the fiction became his vehicle for protests and dissent.

My book really is an examination of how he participated in the coup, and how he believed fundamentally that the Free Officers were going to install democracy, and—once he realized that they were actually installing military dictatorship—the way he dissented, in the editorials and in person, the way that he was jailed, and the way he turned to fiction to express his dissent directly to Nasser.

I hope that my book not only resituates Ihsan as someone worth reading more than just as the writer of love, but someone who was intensely involved in the relationship between the intellectual and the state. In a sense, I think we’ll reevaluate our ideas of this 50s, 60s, and 70s literature. For the people who were engaged in this iltizam (politically committed) writing, it prevented them from seeing what he was actually doing.

I understand that one of Abdel Kouddous’s novels was translated in the 1970s?

JS: The Ministry of Culture commissioned Trevor LeGassick to translate Ana Hurra (I’m Free) in 1978. It was only published in Egypt in the 1970s.

There are some short stories here and there that have been published in journals, but there’s no collection of short stories.

This is a massive project: a book about Ihsan Abdel Kouddous and translations of two of his novels.

JS: I’m also doing a project with the Abdel Kouddous family that I’m really excited about. This got slowed down because of Covid. But we’re also trying to preserve the memory of Rose al-Yusuf. We found an old magazine collector who has a complete paper copy of Rose al-Yusuf. The only copies I’ve found are on microfiche, and the microfiche is in black and white, and I don’t know if you’ve ever looked at copies of Rose al-Yusuf from the 1920s, 30s, and 40s, but color is very important to them. And even the microfiche examples that exist—they’re missing pages, they’re missing issues.

But we found someone who had a complete paper run of Rose al-Yusuf, starting in 1926. So we are looking into the possibility of digitizing it and making it available online, and digitizing it in full color. That’s also part of this project. It’s not just the book, it’s not just the translations, but it’s also trying to archive and preserve Rose al-Yusuf from the time that it was owned by the family. It was nationalized in 1960, so we’re talking about pre-1960. It’s incredible that this hasn’t been done.

*

Read more:

An excerpt from I Do Not Sleep

Ali Shakir: The Silencing of Ihsan Abdel Kouddous

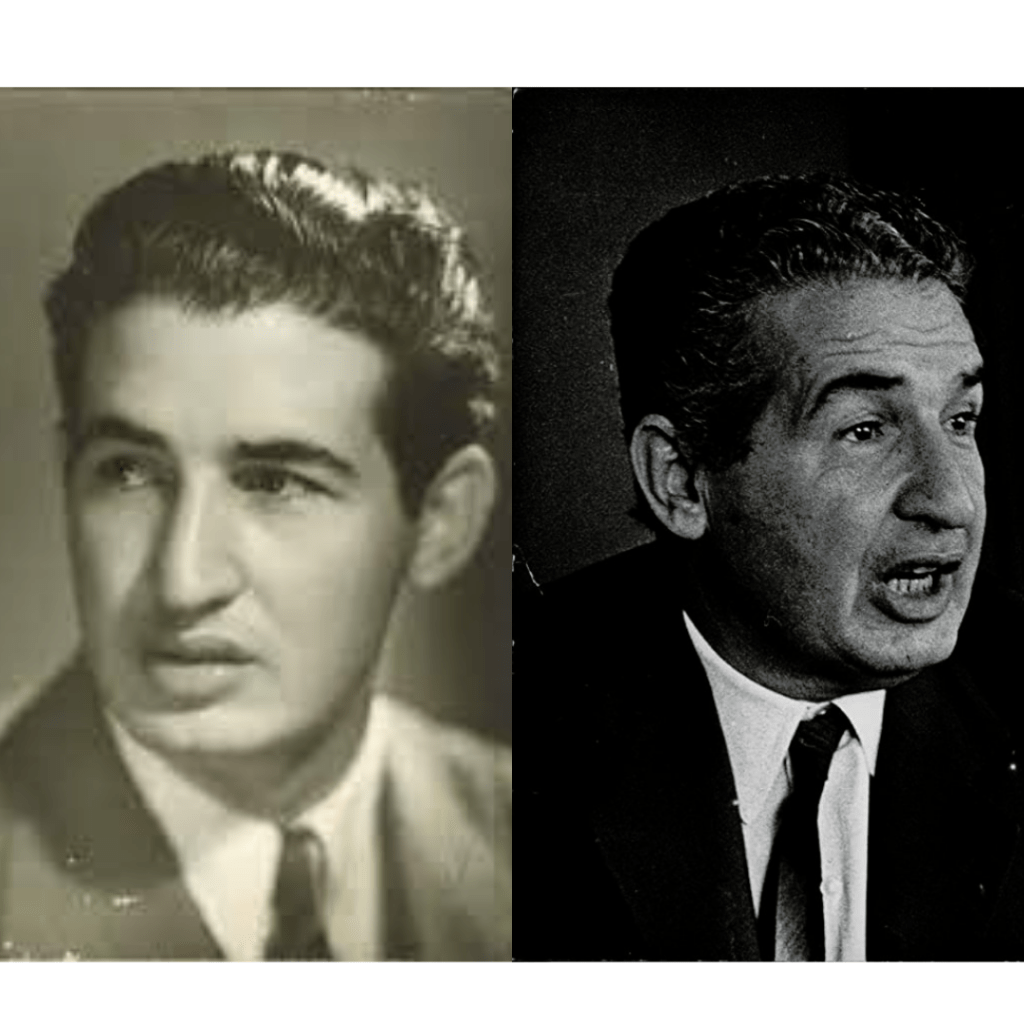

Photos & Films: Ihsan Abdel Kouddous

Two short stories by Abdel Kouddous:

“The Qur’an,” translated by Rahma Bavelaar

“God is Love,” translated by Rahma Bavelaar

Book talks:

January 11, with Jonathan Smolin, Sharif Abdel Kouddous, and M Lynx Qualey

January 27, with Jonathan Smolin and Alaa al-Aswany

Ihsan Abdel Kouddous: Photos and Films – ARABLIT & ARABLIT QUARTERLY

January 4, 2022 @ 7:00 am

[…] A Talk with Jonathan Smolin: On the Intersections of Abdel Kouddous’s Politics and His Fiction […]

On Publication Day, A Look Back: Ihsan Abdel Kouddous – ARABLIT & ARABLIT QUARTERLY

January 4, 2022 @ 10:43 am

[…] A Talk with Jonathan Smolin: On the Intersections of Abdel Kouddous’s Politics and His Fiction […]

Short Story: ‘The Qur’an’ by Ihsan Abdel Kouddous – ARABLIT & ARABLIT QUARTERLY

January 4, 2022 @ 10:45 am

[…] A Talk with Jonathan Smolin: On the Intersections of Abdel Kouddous’s Politics and His Fiction […]